Releasing this on Thursday as tomorrow is Good Friday!

The more time goes by, the more bizarre the whole NAMA experience seems to me. Its scale was so huge, and its nature so unprecedented, that it’s hard to integrate NAMA into our understanding of real estate and cities. Consider a few of the key facts. NAMA acquired real estate assets equal to 47% of Irish GDP (at time of acquisition). Yes, you read that right. That means that back in 2012, for every €2 that were spent in the Irish economy, NAMA had nearly €1 worth of real estate assets. The scale really was colossal.

Moreover, the single largest category of real asset held by NAMA was development land, around a third of its total assets. Development land at that scale represents an enormously important strategic asset for future development, whether that be infrastructure, services or, indeed, housing.

Finally, NAMA was essentially a public body, established via an act of legislation, and yet it claimed to have a more or less purely commercial remit, resisting for a long time the idea that it should have consideration for any criteria other than the bottom line. As NAMA CEO Brendan McDonagh once said, ‘NAMA is a complex business, but it comes down to a simple thing: cash’.

Politicians could hide behind the fact that NAMA was (allegedly) beyond their control, and for the most part the public could not understand what NAMA actually was. It existed in a kind of nebulous political fog, exercisin significant influence over urban development, yet completely impervious to the political process or democratic input. NAMA also, much like everything else about the bank bailout, tore up every rule from the neoliberal playbook. All of a sudden, a huge chunk of the ‘real-estate financial complex’ was nationalised.

NAMA is, of course, still knocking around. But its assets are almost all sold off at this stage, and we may well be at the beginning of a new global banking crisis, so it seems like a good time for some retrospective reflections. This is the first in a multi-part series taking a ‘deep dive’ into NAMA and especially its relationship with urban development and real estate. Between 2013 and 2015 I undertook IRC funded post-doctoral research on this topic, leading to a series of publications (I list them below). This series is based on that research.

In this first instalment of the series, I want to look at what exactly ‘bad banks’ are. One of the interesting things about the NAMA debate, as it played out at the time, is that it was often seen through the lens of Irish exceptionalism - the old ‘an Irish solution to an Irish problem’ line. But in fact, it was an example of an Asset Management Company (AMC), a form of institution which featured very widely in response to the Global Financial Crisis, and indeed in previous real estate financial crises.

The volume of ‘troubled assets’ typically rises dramatically during financial crises as the number of borrowers in distress or default increases and the value of underlying collateral collapses. This can lead to acute problems across the financial sector, undermining the capitalization and solvency of financial institutions, introducing widespread uncertainty in terms of the value of assets and the solvency of banks, and ultimately preventing a return to the issuing of credit (therefore potentially screwing up the ‘real economy’).

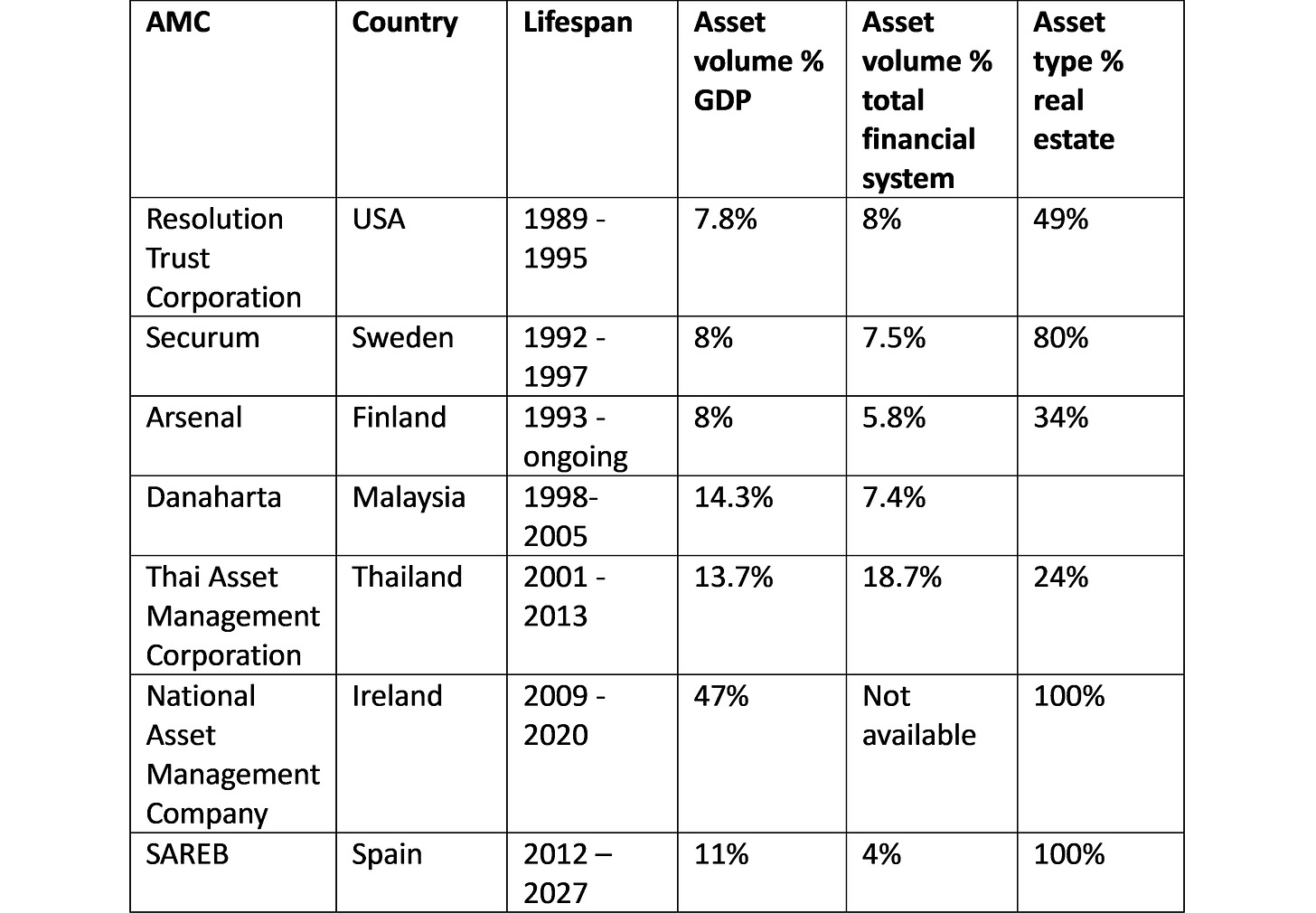

State responses to financial crises, thus, often involve ‘isolating problematic financial assets whose losses and capacity for contagion threaten the broader norms of risk-taking within financial markets’ (Ashton, 2011: 1801). AMCs are one of the most common ways in which governments undertake this task. AMCs acquire distressed real estate assets from banks, take them off the banks’ balance sheet, and then manage them in some way - usually selling them at a discount. The Table below lists some prominent examples.

The objective of AMCs is to maximize the value of the assets they acquire and minimize losses. They thus have an essentially commercial remit in terms of their approach to asset management and disposition.

That said, the scale of AMCs means they have important implications which go beyond simply managing a given set of assets to encompass what economic sociologists call ‘market making’. AMCs have the potential to reboot markets by resurrecting the conditions for ‘liquidity’. Indeed, if they are to ‘maximize’ the value of their assets, this may be required. Crucially, in the Irish case, the scale of the assets they manage also means that AMCs can aggregate assets into large portfolios or packages, attracting global investors who have traditionally not been present in a local market (as argued by Gotham in this brilliant piece).

This was the key role NAMA played. They assembled huge portfolios of assets and used these to attract private equity and hedge funds into the Irish property system.

Gotham’s work shows how the USA’s Resolution Trust Corporation, in the mid-1990s, created Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities for precisely this reason. This gave birth to both a profitable new market, and a new mechanism for connecting local real estate with global flows of capital.

NAMA played a similar role. During an appearance at the Public Accounts Committee in October 2015, Brendan McDonagh (NAMA CEO), stated that: ‘as a major participant in the Irish property market, NAMA did not have the luxury of taking a back seat in terms of instigating market recovery: to get activity going and then to consolidate market recovery, NAMA had to ensure that a flow of transactions was released to the market…’

NAMA wasn’t just a market participant, it was a ‘market maker’.

Lest we forget, NAMA was effectively a public institution (although it was technically majority private owned), in that it was established by legislation and its remit was thus politically defined. So here we have a clear example of the central role of the state in rebooting financialized real estate markets.

Moreover, more than 90% of NAMA’s assets were sold to international financial institutions. Thus NAMA played a huge role in the entry of what some people today call ‘vulture funds’ into the Irish market. To quote McDonagh once again, ‘NAMA’s market activity and deleveraging has contributed to the strong inflows of foreign capital…’

NAMA thus played a role in the globalisation of Irish real estate and gave the state an extraordinary vehicle through which to deepen and extend the ‘financialization of the city’.

As Ashton notes, also in the context of the US, financial crises act as ‘productive moments’ in the process of financialization, in that state responses may generate new forms of government intervention and even new markets, sources of profits and financial instruments, all of which endure beyond the moment of crisis.

In the next instalment of this series (which may be next week or later in the month) we will look more specifically at NAMA’s impact on urban development via the Docklands example.

Events

Not many new events to share this week, except this webinar on ‘decolonizing the city’. I’ll be speaking at an event (provisionally entitled Thinking about Home: Alternative Perspectives on the Housing Crisis in Ireland) on the evening of April 25th, watch this space for further details.

What I’m reading

Instead of the usual list of recent publications, here’s some of the outputs from the IRC project the above article is based on:

Byrne, M. (2016). ‘Asset price urbanism’and financialization after the crisis: Ireland's National Asset Management Agency. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(1), 31-45.

Byrne, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial urbanism after the crisis: Ireland's “Bad Bank” and the redevelopment of Dublin's Docklands. Antipode, 48(4), 899-918.

Byrne, M. (2016). Bad banks and the urban political economy of financialization: The resolution of financial–real estate crises and the co-constitution of urban space and finance. City, 20(5), 685-699.

Beswick, J., Alexandri, G., Byrne, M., Vives-Miró, S., Fields, D., Hodkinson, S., & Janoschka, M. (2016). Speculating on London's housing future: The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes. City, 20(2), 321-341.