In our recent discussion of the report on rent controls by Gibbs et al., we noted that the conventional economic assumption of rental markets as perfectly competitive is problematic (also relevant to the new ESRI report on rent regulation in Ireland). Today I want to continue on the theme of the political economy of rental markets, but take it in a very different direction by developing a Marxian/Georgian critique of the political economy of ‘rent’ in the context of residential housing. This is a conceptual approach I developed in an article a few years ago for the Radical Housing Journal. From what I can tell, nobody appears to have read that article so I have decided to inflict it’s core argument on readers of The Week in Housing.

Today’s topic is dense and, unusually for this Newsletter, it involves a lot of conceptual high-jinks, so we better dive straight in.

Attempts to theorise ‘rent’ and its role within the economy go back to the foundations of political economy. The early political economists sought to account for and explain the operation of land rent by focusing on the specific features of land and those components which distinguish it from other commodities and other aspects of the process of production. Unlike most other commodities, land is inherently scarce, immobile and is not produced for consumption. It is simply a parcel of the surface of the earth, the ownership of which bestows the right to control access and use. In addition, each parcel of land tends to have unique or relatively unique characteristics which cannot be reproduced. As such, land markets are highly local and subject to inelasticity of supply.

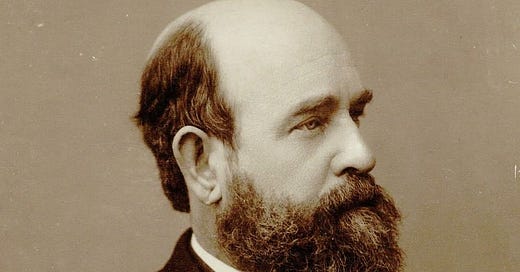

As Ryan-Collins et al. (2017: 38) note, land owners are in a unique position economically because ‘they possess a good that is not subject to the normal laws of market competition’ and as such ‘benefit from additional unearned income…’. Income derived in the form of rent is unearned in that it arises not from any investment or labour, but solely from ownership of a scarce asset. Or as Henry George put it, as a landowner ‘[y]ou may sit down and smoke your pipe...and without doing a stroke of work, without adding one iota to the wealth of the community, in ten years you will be rich.’

My key concern, however, is rent of residential property, i.e. the PRS. Here we can turn to what I believe to be a much neglected text of urban political economy – Logan and Molotch’s (2007) Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. While their focus is on neighbourhoods, their discussion sheds insights relevant to the type of ‘place’ we are interested in here: the home.

Logan and Molotch highlight the fact that in an urban setting: ‘…the attributes of place are achieved through social action, rather than through qualities inherent in a piece of land, and places are defined through social relations…’ (Logan and Molotch, 2008: 45). This ‘social action’ includes public investment in the form of transport networks, infrastructure (e.g. energy, telecommunications and water), and public services such as schools and hospitals. It also includes every day, largely informal social practices, such as simply being a good neighbour, making a place an interesting, safe, friendly environment and so on.

If the value of place is generated locationally and socially, it is the monopolistic nature of land/place that allows owners to ‘capture’ socially generated value in the form of increased property prices and rents. This is a specific form of rent, then, in which monopoly ownership makes possible the appropriation of the socially produced value of place.

So far we have looked at how the category of ‘economic rent’, traditionally applied to land, can be expanded to encompass ‘place’. Now we can look at ‘home’ as a particular kind of place.

Home, as I argued in my series on theories of home, is more than the bricks and mortar which are the legal property of the owner. It is also a nexus or anchor of a set of resources central to social reproduction. At the heart of this is ontological security, which refers to the ‘interrelationships between the physical dimensions of housing (such as safety and security) and the psycho-social dimensions of home, such as privacy, emotional security and identity’ (Hulse and Milligan, 2014: 638). Crucially, ontological security does not emerge spontaneously from the mere fact of inhabiting a dwelling, but rather through practices of place making through which we construct a sense of ownership, control, stability, privacy and safety. This occurs through the changes we make to a dwelling in terms of design and furnishing, through the organisation of our belongings within the dwelling in a particular fashion, and through the routines of work, recreation, socialisation and rest we establish within a dwelling. All of this is a kind of labour which produces the ‘homely qualities’ which transform a house into a home. Thus, in the context of rental housing, ‘home’, at least in part, is produced by the tenant through practical activity, i.e. labour.

In terms of theorising rent, the crucial point is that tenants do not pay simply for access to a dwelling, but rather for continued access to their home. The home, again, is a product of the tenant’s own practical activity and labour, as it is (in part) the result of the practices of home-making and social reproduction which constitute the home as a specific type of place.

These practices are intensely invested in the physical space of the dwelling; in the countless everyday routines, aesthetic choices, and symbolic meanings at work within the four walls of a home. But they also transcend the home as they extend to neighbours, local transport routes, local services, the neighbourhood and the community. None of these things can be easily replaced or reproduced if a tenant loses access to their home. The landlord thus holds a kind of monopoly over the tenant’s home, and it is this monopoly ownership which is the economic basis of rent. Rent is not just an economic relationship, however, it is also a political one: the landlord’s control of the dwelling constitutes a significant form of social power over the tenant’s life and this power is the political basis of the economic extraction of rent from the tenant.

Finally, it is important to stress that while there is an inherent antagonism associated with what I call ‘the residential rent relation’, this manifests differently in different contexts. For example, in a highly regulated rental sector a tenant may enjoy robust security of tenure, the right to make changes to the dwelling and rent increases may not be at the discretion of the landlord. In such an instance, the antagonistic dimension of the rent relation may not manifest at all.

What are the implications of this approach for the contemporary PRS? To be quite honest, I am not sure. But it does suggest that the politics, power relations and inequalities of the PRS run much deeper than is often assumed, and it possibly helps us to understand whey renters are so pissed off.

Events

The Focus Ireland Lunch Time Talks series continues, and I am really looking forward to this next instalment as I will be responding to Richard Waldron’s presentation. Richard has been doing some fascinating work on precarity in the Irish PRS of late (see this paper), so it will be really interesting to hear about his work on tenants’ coping strategies in the context of Covid. On April 28th, Locarn Sir will look at housing data in the Irish context as part of the #SimonTalks seminar series.

What I’m reading

Two really important new reports from the ESRI this week. One looking at migrants, housing and integration and another looking at rent regulation. On the international front, we all love to talk about the ‘Vienna model’, but we often know little about the Austrian capital’s longer history of urban development. A new paper by the always interesting Justin Kadi looks at Vienna’s ‘long history of gentrification’.

Finally, here is a bibliography of the work the above analysis draws on:

Andreucci, D., García-Lamarca, M., Wedekind, J., & Swyngedouw, E. (2017). “Value grabbing”: A political ecology of rent, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 28(3), pp. 28-47.

George, H. (1884). Progress and poverty: An inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions, and of increase of want with increase of wealth, the remedy. W. Reeves.

Haila, A. (1990). The theory of land rent at the crossroads. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 8(3), pp. 275-296.

Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defense of housing: The politics of crisis, (London: Verso Books).

Logan, J. R., & Molotch, H. L. (2007). Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. University of California Press.

Ryan-Collins, J., Lloyd, T., & Macfarlane, L. (2017). Rethinking the economics of land and housing, (London: Zed Books Ltd).

Smith, N. (1979). Toward a theory of gentrification a back to the city movement by capital, not people. Journal of the American planning association, 45(4), pp. 538-548.

Smith, S., Le Grand, J., & Propper, C. (2008). The economics of social problems. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ward, C., & Aalbers, M. (2016). Virtual special issue editorial essay: ‘The shitty rent business’: What’s the point of land rent theory?, Urban Studies, 53(9).