I recently listened to this interview with Sean Keyes on Rory Hearne’s Reboot Republic Podcast. One thing that struck me was a deceptively simple, but actually quite revealing point made by Sean. He argues that the debate around housing, and especially the question of markets and market supply, boils down to a simple dichotomy. Those who we might put, for the want of a better term, in the category of ‘market friendly’, support both market supply and non-market, i.e. state supported, supply. In other words, they support all forms of supply. In contrast, many ‘progressives’, who typically place much greater emphasis on the role of non-market housing, support non-market supply but are sceptical, if not down right opposed, to market supply.

As Sean and Rory note in their conversation, this represents almost a reversal of how housing politics broke down in the past. Back in the 2000s, pretty much everyone accepted that most, indeed virtually all, housing supply would be market supply. The difference was that while progressives typically argued for the role of social housing in addition to the norm of market supply, neoliberals (i.e. the ‘market friendly’ cohort at the time) were supportive of market supply but sceptical, if not downright opposed, to social housing supply, or indeed other forms of non-market supply.

As Keyes notes, the ‘overton window’ has shifted.

One consequence of this shift is that ‘market friendly’ commentators can now declare that they are in favour of all supply, thus allowing them to label progressives as ‘supply sceptics’ or even ‘NIMBYs’. In practice, we see this when progressives are criticised for opposing specific developments, for opposing specific housing typologies (build-to-rent, co-living, purpose build student accommodation) or indeed for questioning/criticizing econometric analyses which identify a correlation between increased supply of rental housing and lower levels of rent increases.

For progressive housing commentators (which I suppose is how I would describe myself), this is somewhat tragic as the whole issue of supply should be progressives’ ‘home turf’. In short, progressives should ‘own’ the supply argument. If progressives allow themselves to be painted as anti-supply, it will be what the kids these days call a ‘self-own’.

The reason progressives should be natural supply cheer-leaders is because market supply has always been problematic and is beset, for a number of structural reasons, with difficulties. Space prevents a full discussion of all of these issues but some of the main points would be:

- Housing/land markets are inherently local and supply constrained

- Construction work has not enjoyed much in the way of productivity gains, when compared to more standard markets

- Housing supply is constrained by planning (I don’t mean that Irish planning policy is specifically constraining, I mean in general all housing systems involve planning constraints due to the potential for enormous social and environmental damage associated with housing’s ‘externalities’).

- Housing is deeply interconnected with the credit system, which intensifies the boom/bust dynamic and can lead to overshoots but also lags in recuperating supply (as we know all too well in Ireland)

- Housing is both a good that people consume and an asset that people invest in and speculate on, which means even when supply outstrips demand, under some conditions, prices can increase.

In short, although it may be true that, ceteris paribus, an increase in supply is associated with a level of price inflation that is lower than what would have been the case absent that increase, empirically (i.e. in reality) supply often does not respond well to demand and therefore supply/demand imbalances can be sustained over the long term in a way that does not occur in many other products.

The state, on the other hand, can support stable levels of supply in a way that responds to demand. There are also loads of reasons why the state is better positioned re housing supply. Some of these include:

- The state usually owns very large amounts of land;

- The state can undertake active land management over the long term, e.g. putting in place infrastructure for several decades down the line

- The state can coordinate housing delivery with other public policy objectives, such as climate change, transport, community integration, etc.

- State investment in urban development leads to unearned windfall gains for private land owners, so if the state can recoup or manage this somehow it makes sense

- The state can borrow cheaper than anyone else

- The state can ensure affordability, by controlling how rents or house prices are set, in a way that the market can’t/won’t

To be clear, I am certainly not arguing that market supply has no role and only the state should provide housing. The point is that, given all of the above, how can we find ourselves in a position that progressives can appear, or be painted as, ‘weak’ on the topic of supply?

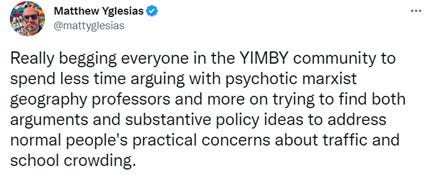

Part of the reason we see terms like NIMBY etc. being thrown around a lot is that it is a convenient way of dismissing what Mathew Iglesias recently called on twitter ‘psychotic Marxist geographers’. Lol.

But I think there is more to it than that. I think there are two other relevant issues. First, having spent a lot of the 1990s and 2000s on the defensive, and needing to challenge neoliberalism at every turn, progressives often fall victim to a rhetorical tic involving an excessive tendency to paint the supply of market housing as not only being not the solution, but being in fact the problem. There is an element of truth to this (for example in the financialization literature), but it is very easy to overstate this case to the point it becomes counter-productive.

Second, progressives have shied away from putting forward a progressive approach to market housing, for example engaging with issues like viability or finance (Robert Sweeney’s piece on viability in these pages notwithstanding).

Third, there is also a sense in which there is a ‘zero-sum’ nature of housing at a local level, because at a local level land is inherently constrained. So for example, if you build a load of BTR and student accommodation in D7 than the neighbourhood will be largely defined by these housing typologies, and the socio-economic groups that cam access that type of housing. Therefore, while in the abstract you can be pro both market and state housing, in terms of local politics it can very easily become an either/or.

The upshot of all this is that progressives need to shift the terms of the debate to ‘own’ the supply issue (to be clear, I acknowledge that many progressive housing policy commentators are already working in this direction, and indeed are a lot more effectively than I am!). This involves in part dialing down the market scepticism, having progressive policies on the delivery of market housing, and trying to reframe the terms of the debate such that we are not baited into the position of denying that the supply of housing is good.

Events

A reminder that the Housing Agency are launching a new piece of research on residential satisfaction on February 8th. On February 20th, the ESRI launch a new piece of research on housing and childhood outcomes.

What I’m reading

This very informative blog from Focus analyses the eviction ban and homelessness and is well worth a read. There has been very little empirical research on institutional landlords, so this new piece is very welcome.