Is housing in Ireland unaffordable? The answer would seemingly be a resounding yes. But, as usual, the question is trickier than it might first appear. There are basically three ways of answering this question at a general level: coming up with some kind of objective measure of housing unaffordability (which is quite tricky in itself, see my earlier post), comparing Ireland to other countries, or a combination of the two. I recently got around to reading a fascinating ESRI paper from last year, by Wendy Disch and Rachel Slaymaker, Housing affordability: Ireland in a cross-country context, which takes the last of these three approaches.

Overall, the authors find that Ireland comes out pretty good – we have some of the best affordability outcomes of comparable European countries (meaning Western European). Reading the research, it is hard not to come away feeling that the argument that housing in Ireland is much worse than most places is plain wrong. Digging into the detail, however, we can see that there is more to this story than meets the eye. In particular, it seems that while average housing costs in Ireland are comparably low, high housing costs in Ireland are particularly concentrated. Moreover, the fact that Ireland fares comparatively well has nothing to do with the fact that house prices and rents aren’t as high as we think, and everything to do with the enormous amount of money the Government spends to support affordability. I am reminded a bit here of the well known argument that while Ireland has average levels of income inequality, our tax and welfare system has to work very hard to achieve this because market incomes are particularly unequal. It seems something similar is going on in housing.

A couple of caveats before we get going. First, in a sense it shouldn’t be too surprising that Ireland fares well as we are a high-income country, and therefore even though we have high housing costs this is somewhat offset by incomes. Second, comparative approaches can be very useful analytically, but we should be cautious about how they are used politically. Sometimes, researchers (especially of the ‘graph bro’ type on Twitter) can be fond of using comparative data to invalidate people’s lived experience. But it is not at all clear that cross-country comparisons are a good way to make sense of people’s experience of inequality or injustice. For most people, the relevant factors in terms of how they experience inequality are going to be things like the level of suffering it generates for them, how they compare to other cohorts within their society (see Wilkinson and Pickett’s work) and whether things seem to be getting better or worse (i.e. comparisons over time).

With that said, let’s jump in. Most of the comparative data presented in this research is from EUSILC 2019. However, it also presents some additional data available from EUSILC 2021 which gives a bit more detail on Ireland in terms of tenure breakdown and things like that. The authors mainly look at income ratio measures looking at housing costs as rent payment or mortgage payment, and use various thresholds (I focus here on the 30% of net income on housing costs affordability threshold).

With regard to the overall housing cost picture, on average Irish households pay around 20% of net income on housing cost (rent or mortgage), lower than most comparable countries. On average, in other European countries 20% of households pay more than 30% of net income, in Ireland the figure is 15%.

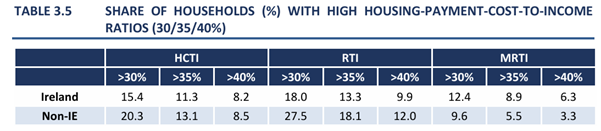

The below table breaks down housing cost-to-income ratios looking at various thresholds, and covering rent-to-income and mortgage-to-income. As can be seen, overall Ireland comes out well. In the below, we can see that affordability is somewhat worse for mortgage holders in Ireland than elsewhere, which the authors attribute, in part, to the Celtic Tiger legacy of loose credit. However, when looking at the rent-to-income data, it is extremely important to note that this includes all renters, i.e. market price renters, social renters and renters in receipt of subsidy (HAP, RS, RAS). I’ll return to this below.

Looking just at the most economically vulnerable households, a rather high figure of one third of Irish households pay more than 30%. However, the figure for the rest of Europe its even higher at 55%. Part of the reason why low-income households in Ireland fare well by comparison is that, somewhat surprisingly, outright ownership is most common in Ireland for households in the lowest income quintile, with some 54% owning without a mortgage (mainly because there are so many pensioners in this cohort, who are mainly homeowners).

As can be seen above, households in the first income quintile come out best, while households in quintiles 3, 4 and 5 actually have higher than average housing costs.

Looking just at renters (including all categories of renters), they have the lowest rent-to-income ratio of any of the comparison countries. Again, those in the lowest income quintile fare best, with renters in the 4th and 5th income quintiles facing rent-to-income ratios on average 2/3 percentage points higher than similar European countries.

Indeed, the share of renters in the 4th quintile who pay more than 30% on rent is higher in Ireland then elsewhere (14 Vs 3%) and so it is in the third quintile (16 Vs 9%).

As can be seen below, if we look just at renters who pay market price rents (i.e. are not in receipt of any government support) their average housing costs are significantly higher than both mortgaged households and renters in receipt of a support (social housing, HAP, RS, RAS). Affordability challenges, it seems, are concentrated among middle-income, market-price renters, who on average pay more for housing than either mortgaged households or supported renters, and who spend more on housing costs than their European peers.

Looking more closely at renters in receipt of a subsidy (HAP/RS), they had an average rent-to-income ratio of 15% in 2021. Without subsidies, these households would have paid nearly 43% of income on rent, and nearly half would have paid more than 40%. So, HAP/RS are very effective from an affordability point of view, and in fact the authors note that rent subsidies in Ireland are three to four times greater than what is offered by most countries. On average, households in receipt of rent subsidies in Ireland in 2019 received €690 per month, the highest payment across comparable European countries.

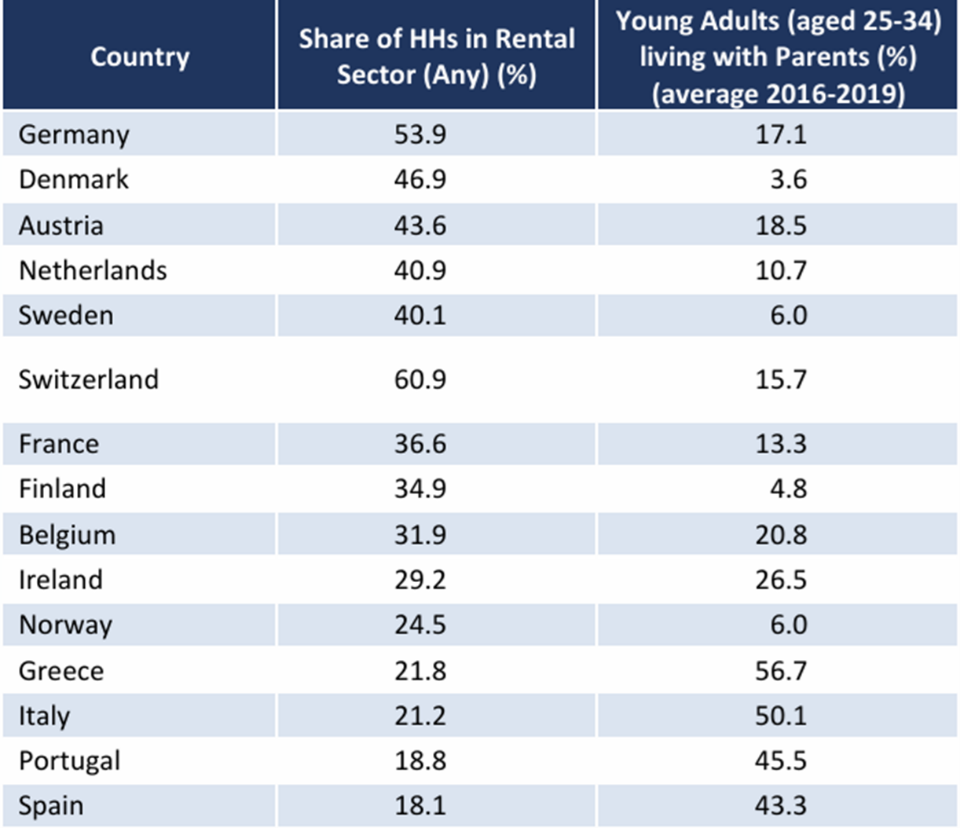

A number of final points before drawing this all together. First, Ireland has one of the biggest ownership gaps between younger (under 40) and older cohorts (second only to Greece), suggesting growing issues accessing homeownership, in part related to affordability but also of course to macro-prudential rules.

Second, the authors note that affordability measures don’t capture people who have not been able to form households because they can’t afford to, a case in point being young people living at home, of which Ireland has very high rates.

Third, some vulnerable cohorts, like lone parents, are more likely to have high housing costs in Ireland than elsewhere.

Drawing all this together we can say that Ireland does not have a general housing affordability problem. However, this is not because rents/house prices are low. Rather it is because for historical reasons there are a high proportion of outright owners, especially in the lower quintile, and because Government interventions are particularly extensive. This is true both for social housing, where rents are lower than elsewhere, and in relation to generosity of rent subsidies, which are much higher than elsewhere.

Moreover, the fact that housing affordability is so dependent on Government intervention means there are three specific (but somewhat overlapping) ‘pinch points’ in terms of housing affordability. First, market price renters, who have by far the highest housing cost-to-income ratios amongst Irish households and also fare worse than European counterparts. Second, young adults who are not able to form a household and thus remain at home. And third, aspiring younger first-time-buyers unable to access homeownership (and hence either renting at market price or remaining in parental home).

Events & News

The Housing Agency are organising a conference on AI and housing innovation. The good people at TUD’S Property, Land and Construction have launched a new academic journal. The European Union has appointed its first ever commissioner for housing. The Urban Political podcast is always worth a listen, check out this recent episode on racism and social mixing policies. And finally, if you have every wanted to own some fine art, here is an opportunity to do so while supporting the Simon Community.

What I’m reading

The Social Democrats have launched their Affordable Housing Plan. A really interesting new paper from my colleague Bryan Fanning looks at Policy and Political Responses to Ireland’s Refugee Crisis. This looks like a very important report looking at the role of investment demand in house prices in the UK - Josh Ryan-Collins is always worth a read. The Local Government Information Unit have published a briefing on the report of the Housing Commission (only available to members I’m afraid).

“Affordability challenges, it seems, are concentrated among middle-income, market-price renters, who on average pay more for housing than either mortgaged households or supported renters, and who spend more on housing costs than their European peers.”

This is dead right.

There is a kind of middle-income trap where your income is too low to allow you to buy but too high for you to qualify you for housing supports. You’re stuck in the PRS and it’s particularly pronounced in and around Dublin.

Maybe I am cynical but a lot of people in Ireland’s NGOs and media are in this cohort which is why it gets a lot of bandwidth .

It’s not clear whether the above cohort is stuck renting for life or whether it’s just a lifecycle phase, perhaps a prolonged one. You would really need good longitudinal analysis for this and no one carries it out to my knowledge.