Last week we looked at the big picture issue of the relationship between financial and housing systems in the UNECE, UN-habitat, and Housing Europe report #Housing2030: Effective policies for affordable housing in the UNECE region. This week I want to talk about three more ways governments can influence housing and financial markets covered in the report.

The first is the role of public or quasi-public financial institutions. The report looks at the European Investment Bank and the Council of Europe Development Bank. Neither of these institutions are state funded. Instead, they raise funding by borrowing on international capital markets. Due to the very low risk associated with these institutions, they have extremely high credit ratings and can access very low cost finance (i.e. they can borrow at very low interest rates). The EIB, for example, can borrow to finance social housing, refugee accommodation and care homes.

Financial institutions like these can lend to providers of social/affordable housing. By providing low cost finance, they support both the volume of housing provision and also keep costs low, making it easier to keep housing affordable. Private developers typically have reasonably high borrowing costs and of course require a significant profit margin. Social/affordable housing provided in a non-market fashion and financed via the EIB or the CEDB are thus much more cost effective. In the Irish case, the Housing Finance Agency borrows from the EIB and in turn lends to Approved Housing Bodies (Robert Sweeney has a new piece this week on supply and affordability in the Irish context that is well worth a look).

As in the case of the interest rate subsidies, discussed last week, what is interesting here is the ‘pathway’ that is created to channel private finance away from destructive forms of investment (like rentierism and property speculation), towards affordable housing. The availability of these channels raises the question about what potential may exist for a massive expansion of this form of intervention. If such funding was made available for the acquisition of land and the provision of housing at a very large scale, a wholescale decommiodification of housing markets could be undertaken . Of course, if this were to happen the associated borrowing would need to be repaid, which means that rents or house prices would need to be set on a cost recovery basis (as is the case in Ireland’s new cost rental sector). Singapore is an example of such an approach: 90% of land there was compulsory purchased by the Government in the 1950s and 1960s and between 80% and 90% of the population live in public housing (I hope to return to Singaporean housing policy in the future).

The report also discusses two ways of directly intervening in housing costs: rent subsidies and rent regulation. Rent subsidies have become a much more important part of many housing systems internationally and the associated costs have grown rapidly. For example, the report notes that:

“[I]nvestment in affordable housing declined by 44 per cent, from EUR 48.2 billion in 2009 to EUR 27.5 billion in 2015. Over the same period, expenditure on housing allowances increased by 58 per cent from EUR 54.5 billion to EUR 80.8 billion.”

Rent subsidies are thus a popular policy choice. But are they a good one? The report highlights evidence from an international review that found ‘Strong evidence that a proportion of these subsidies is capitalized into higher rents in the private rental market, which thereby represents a “dead weight” loss for the state’. This is especially the case in housing markets where supply is constrained (like ours), and therefore subsidised demand tends to get captured by landlords in the form of higher rents.

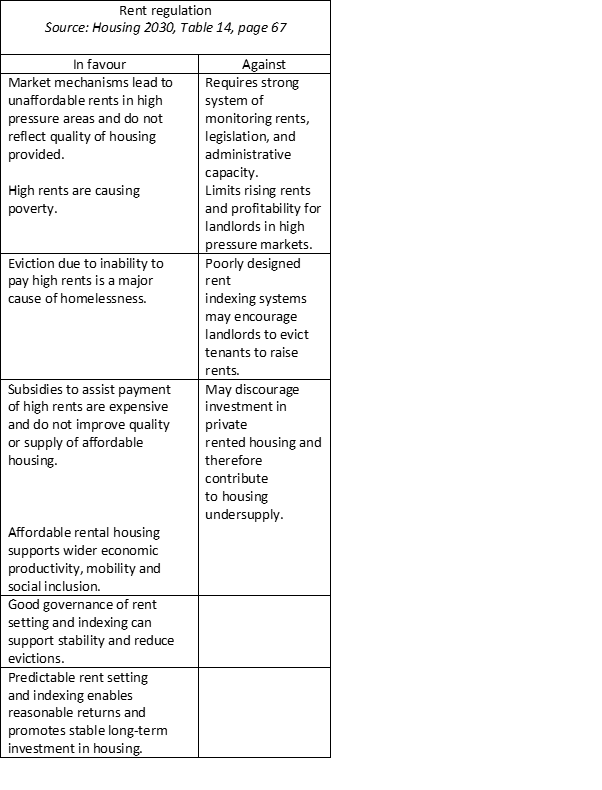

The second category I want to look at is rent regulation. The report notes that rent regulations, depending on how they are structured, can affect supply, but it also cites research which shows that ‘moderate rent controls do not seem to significantly affect supply’. They make the argument that:

“[W]hile rent controls can affect supply, this is true for most housing market regulation, including macroprudential rules, property taxes and land use planning. Rent regulations should therefore balance controls against ensuring everyone can access decent housing at an affordable price”.

This is a really important point. Rather than adopting one of the two binary positions (i.e. that rent regulations are always good because they have no effect on supply, or the contrary position that rent regulations are always bad because they always have a negative effect on supply) we need to look at the trade-offs in specific contexts and based on specific public policy priorities.

Taken together, the report provides a wide variety of policy tools that do more than just address issues in the housing system; they offer the possibility of restructuring how housing, finance and land interact to create an altogether different housing system. The report is symptomatic of a radical shift in thinking around housing policy that has been going on for the last number of years as many different countries are running into major affordability problems. It will be very interesting to see how this develops in future years, and no doubt this report will play a big role in that process.

Events

An important event in the housing calendar will take place November 8th-12th: the Housing Agency conference for 2021. You can find out all the details and register here and check out the programme here.

The Empty Homes initiative are organizing what looks like a really interesting seminar on an issue very much in the spotlight here in Ireland. The seminar will look at vacancy and under-utilization of housing in the Greater Manchester area and will take place on October 21st. Two weeks ago the Housing Agency held a seminar looking in detail at the recent changes to Part V housing, a video of the event is now available here.

What I’m reading

The first progress report for Housing for All was published this week and the LDA published this presentation of survey findings on cost rental housing, I presume a full report will be published a some point. This week I also wanted to share some of the research I came across in the #Housing2030 report:

Ryan-Collins, J. (2019) Breaking the housing–finance cycle: Macroeconomic policy reforms for more affordable homes, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space.

Van Heerden, S., Ribeiro Barranco, R., & Lavalle, C. (2020). Who owns the city? Exploratory research activity on the financialization of housing in EU cities. Brussels: European Commission Joint Research Committee. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eurscientific-and-technical-research-reports/who-owns-city-exploratory-research-activity-financialization-housing-eu-cities.

Gibb, K (2018), Funding New Social and Affordable Housing: Ideas, evidence, and options, https://housingevidence.ac.uk/publications/funding-new-social-and-affordable-housing/

Gibb, K and Haynton, J (2018) Overcoming Obstacles to the Funding and Delivery of Affordable Housing Supply in European States https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/2018.10.22_overcoming_obstacles_to_the_funding_and_delivery_of_affordable_housing_supply_in_european_states_1.pdf

Whitehead, C., & Williams, P. (2018). Assessing the evidence on Rent Control from an International Perspective. London: London School of Economics. https://www.lse.ac.uk/business-and-consultancy/consulting/consulting-reports/assessing-the-evidence-on-rentcontrol-from-an-international-perspective.