Gloomy outlook for the PRS (unless you're an institutional landlord)

The Week in Housing 02/12/22

There have been a host of new publications relating to the Irish PRS over the last couple of weeks, including the RTB Annual Report 2021 and latest rent index, the latest Daft report, and the latest Hooke and MacDonald report on residential investment (not publicly available as far as I know, but possibly by request). So what do we know now that we didn’t know two weeks ago?

The first thing that strikes the reader is the disconnect between the Hooke and MacDonald report, which focuses on institutional investment in the PRS (what they, along with most of the industry, now term the ‘multifamily sector’), and the other three reports, all of which look at the rental sector as a whole. Based on their analysis of institutional PRS investment Q1-Q3 2022, Hooke and MacDonald’s research suggests things look rather rosy. The PRS represented the biggest asset class in the Greater Dublin area over the period, accounting for 37% of the estimated €3.5bn investment. Of the 2,792 ‘multi-family’ units sold in Qs 1-3 in Dublin, 85% were new build.

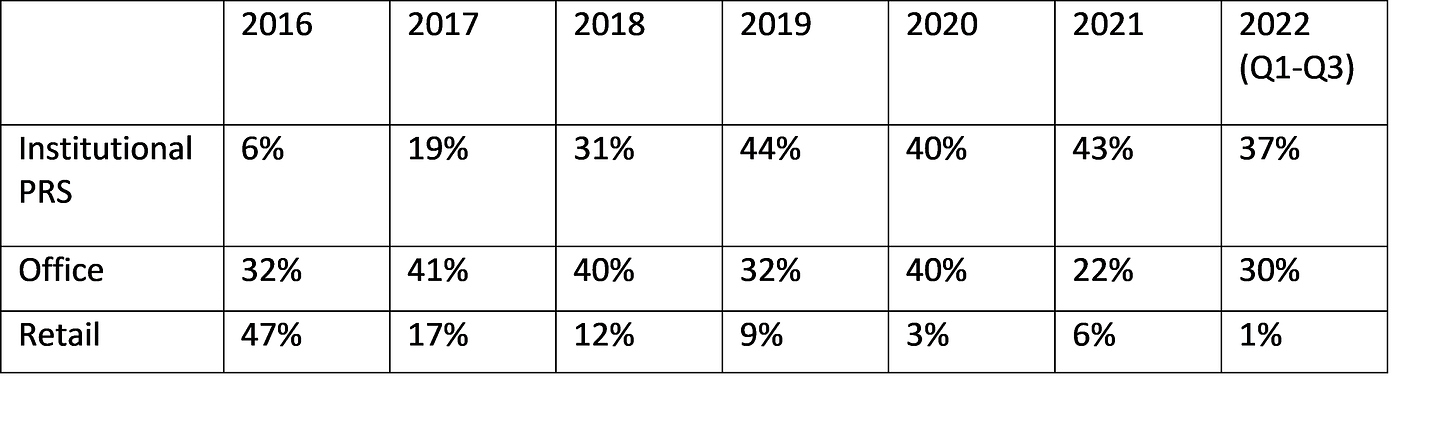

These figures are even more significant when we recall that just 6 years ago, the PRS made up only 6% of total investment spend on real estate assets in the Dublin area, as depicted in the below table.

Source: Hooke and MacDonald. 2022. he Residential Investment Bulletin Greater Dublin Area Q1-Q3, 2022.

Moreover, the future for PRS investment looks bright in that the supply/demand imbalance looks set not only to remain, but to deepen, primarily due to demographic trends. The Hooke and MacDonald report notes that:

The Irish National Planning Framework’s (NPF’s) population projections provided for a net in-migration of 8,000 people per annum for the first five years of the plan, and 12,500 per annum thereafter. For the first six years of the Plan to April 2022, this would equate to 52,500. The preliminary 2022 census results confirm that for this five-year period the State had a net in migration of 190,333 people. Accordingly, the NPF’s in-migration estimate is just 27.58% of what has actually occurred – showing a six-year deficit of 137,833 people. This is in a period which included a cessation of movement and international relocation during the Covid-19 pandemic.

This suggests that the housing needs of the state are far in excess of the average 33,000 homes per year planned for in Housing for All – the report reckons the annual requirement is closer to 50,000.

The Hooke and MacDonald report does note some of the challenges in the sector, noting that ‘some investors are adopting a pause approach to investment, until they see how the political and interest rate environment and markets develop’. The main relevant challenges are rising interest rates and changing financial market conditions, which I’ve written about recently. No mention is made of tech sector layoffs, the shift to work from home or any other labour market related challenges. But they also note continued strong demand for investment in Dublin based on their interactions with international financial institutions (of course we should note that Hooke and MacDonald are themselves property market participants, rather than an independent third party in all of this).

When it comes to the small-scale landlord sector, the H&M report agrees with the consensus that there has been a consistent decline in investment. They note the following factors driving a ‘landlord exodus’:

· The 50% marginal tax rate on rental income;

· Many of the properties in the Irish rental market owned by smaller investors would now be over 15 years old and are requiring increasing amounts of spend on repairs and upgrading;

· Increasing interest rates have put a larger burden on the owners;

· As house prices have been rising, with loan balances reducing, many rental properties are no longer in negative equity.

One thing they don’t mention (along with everyone else) is the Capital Gains Tax for landlords who purchased around 2014.

Interestingly, they argue that any attempt to woo such investors back into the market is ‘naïve’, as small-scale landlords, at least in the current climate, have ‘no intention of returning’. This line of thinking may possibly help to explain why the Government decided not to provide any significant change to the tax regime for small-scale landlords in the recent budget. The implication of all this is, presumably, that institutional investors are the only show in town.

So far, so gloomy. But it gets a hell of a lot worse when we look at the new data on rents. The Daft report, based on a sample of advertised rents, found that rental inflation has broken not one, but two new records. The nationwide average annual rent increases for Q3 2022 hit a new high of 14.1%, while the quarterly increase was also a new high of 4.3%. Rental inflation was pretty evenly spread over the past year: 14.3% in Dublin, 14.5% in other cities, and 13.8% outside cities. To top it all off, on the first day of Q3 2022 there were just 495 homes on the market (i.e. on Daft). Importantly, Lyons (unlike most commentators), notes that this is partially due to declining supply but also due to a post-covid ‘resurgence’ in demand.

The RTB’s rent index for Q2 2022 tells much the same story: an 8.2% increase in national average rents over the past year (for new tenancies only). Average rents are now 42.5% higher than their Celtic Tiger era peak! More troublingly still, the number of new tenancies registered decreased by 16% compared to the same period last year (see below table showing evolution of registered tenancies since 2005, including latest figures).

There are a couple of other interesting things to note in relation to the RTB. First, by the end of 2021, 132 investigations had been initiated into non-compliance of landlords, based on the new powers conferred on the RTB during Eoghan Murphy’s reign. This led to 29 sanctions by the end of 2021, almost all of which were for breaches of the rent control regulations (which the RTB is prioritising). Moreover, the RTB began a campaign ‘to identify tenancies where higher probabilities of non-compliance with rent setting may have occurred’, on the basis of which ‘over 2,700 landlords were contacted’. The whole non-compliance issue remains something we don’t have comprehensive data on, but with rents increasing the way they are it is very hard to draw any conclusion other than that non-compliance is widespread. It is interesting to see the RTB make use of its new teeth, as only a few years ago the approach was very much one of ‘supporting landlords to comply’ through education. Second, the RTB has made a big contribution in terms of research and evidence over the last year or so, launching their Research and Data Hub and initiating their Rental Sector Survey reports, as well as re-jigging their tenancy register. A lot of credit is due on that front.

It's hard to know how to respond to all of this bad news, there appears to be no limit to how bad things can get in the PRS. Although, as wise man once said, ‘the grass is always greener’…

There will be no Newsletter next week as I am taking a few days leave.

Events

The recordings form last week’s Housing Agency conference are now available in full, watch here. On December 7th, Minister Darragh O’Brien will launch Threshold’s annual report, and The Simon Community’s annual report will be launched on December 8th. Next Tuesday, December 6th, the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice will launch a new book on ‘practical environmental care’.

What I’m reading

Check out this new installment of the Housing Agency’s data insight series. Thanks to NUIG’S Padraic Kenna for letting me know about two recent publications on the subject of land value capture, this new book, and this compendium of land value capture policies put together by the OECD. This very interesting piece in the Currency looking at the structural nature of the Irish housing crisis within a global economic perspective is well worth reading.

Thanks again for your excellent post.

One point though, evasion of the rent caps may not be as common is thought. From reading landlords’ forums, they don’t seem to increase the rent for ‘good’ sitting tenants. It is too much hassle, annoys the tenant and the increase is hardly worthwhile anyway (rent of €2,000 x 2% = €40 gross, €20 net after tax).

Therefore, they increase the rent when the tenant leaves and are entitled to backdate it. This works as follows:

1. Tenant has been in situ for three years (average length of leases, apparently) and leaves

2. Rent not increased during that period

3. Landlord now entitled to impose a 6% increase on the new tenant

4. This then seems to come across in the statistics as a 6% increase on a new tenancy– it is not, it is a backdated 2% per annum increase

Now I’ve no idea how frequent this practice is and there is nothing stopping the landlord in the above example taking the 6% which he or she is entitled to and lumping a further 20% on top of that. All I am saying is that both the RTB and the Daft.ie statistics may not be granular enough to work out exactly what is going on – some of the increase may be this ‘backdating’.