In last week’s discussion of the recent Housing Europe report Cost-based social rental housing in Europe, we saw how different cost rental systems are characterized by varying financing arrangements. This week I want to return to the Austrian, Danish and Finnish systems to focus on rent setting and the challenges associated with affordability of rents in all three cases. I’ll start by summarizing the report’s analysis of rent setting across the three countries, including an example in each case.

Austria

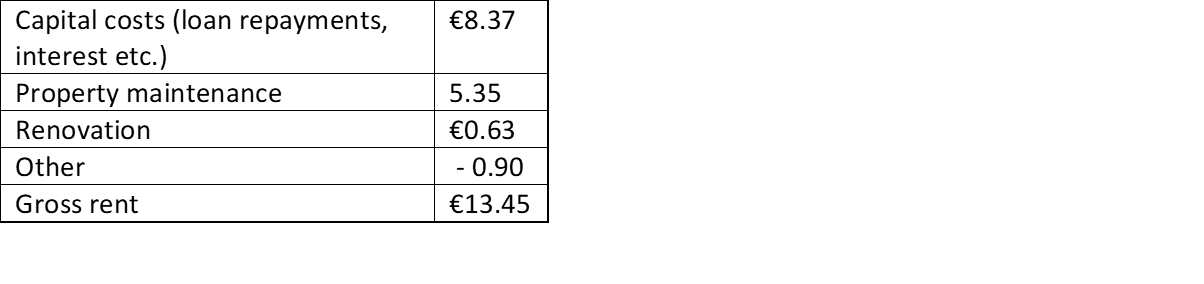

Based on the financing model discussed last week, with its balance between public loans, private loans and equity, the Austrian cost rental sector can achieve some reasonably low rents. The report provides the following example:

Recently built apartment in Vienna, about 86 sqm, utilities not included

Allocation in Austria is primarily via a waiting list system. There are income thresholds but approximately 80% of households qualify. In recent years there have been growing challenges for low-income households in accessing LPHA cost rental housing. This is in part because of rising rents and the growing requirement for tenant deposits. Some commentators argue that these challenges are a result of increasing land prices and general scarcity of land in areas of high demand, such as Vienna. In practice, the municipal housing sector (which is also cost rental and represents around 7% of housing stock) often accommodates more vulnerable households, in part because it is typically older stock with lower rents and in part because of municipalities’ obligation to meet housing need.

Denmark

Recent apartment development, Greater Copenhagen

Once again land costs are a growing challenge. As far as allocation goes, this is a universalist model with no income criteria, allocation taking place based on waiting lists (or occasionally lotteries). However, in Denmark, municipalities retain the right to allocate 25% of new cost rental dwellings to households in need. This supports access of low income and vulnerable households.

Finland

Recently completed Helsinki apartments. In this instance costs are given per square meter.

Gross rent here is €13.45 per square meter. If we compare this to the rent in the Austrian example, which is for an 86 square meter apartment, rent works out at €1,156.7 per month, very similar to the Danish example. Allocation includes a waiting list system, but there are also needs-based components with a focus on those in urgent need of housing, such as homeless individuals, private renters whose lease is being terminated, adults still living at home etc.

The challenge of affordability

In all three cases, rent setting is similar. It is made up of capital costs (including land acquisition, development and financing costs), property maintenance and management, and renovation/reserve funds. What is notable in all cases, though especially Denmark and Finland, is that rents are not particularly cheap. In all three cases, for example, rents are much higher than the approximately €250 per month average rent paid by Irish social housing tenants in our income-based rent setting system. The Austrian example has a significantly lower rent level. It would be interesting to look into exactly what accounts for the difference, but it is likely related to the much greater role of both public loans and equity in the Austrian model, as discussed last week.

To my mind, and this is an argument I hope to develop much further in future issues of this newsletter, moderately high rents are not a major problem in cost rental housing, or at least not the major problem many Irish commentators seem to think they are. Nevertheless, in all three cases low income households face challenges in accessing cost rental housing. To address these, a number of mechanisms are used:

Denmark: 25% of new units are allocated by the municipality, ensuring prioritized access for more vulnerable households. In addition, cost rental tenants can access housing supports (i.e. rent subsidies). Some would argue that this means cost rental tenants are subsidized twice, but in my view any sensible commentator can see that this is greatly preferable to the absurd situation of subsidizing private landlords en masse. To my knowledge, all cost rental models include a rent subsidy of some sort which is accessible to low income tenants (this in turn reduces the risk associated with cost rental housing by reducing the potential for rent arrears and for difficulties tenanting units during recessions).

Austria: low-income tenants can access a low-interest public loan to support payment of a deposits, where required, and rent subsidies are also available.

Finland: unlike the other two models, rents can be equalized across developments so that revenue from older developments can be used to subsidize more expensive newer developments, thus helping to stabilize rents. This contrasts with Denmark and Austria, where older stock is typically significantly cheaper. Moreover, cost rental housing is owned (for the most part) my municipalities who incorporate a needs-based component into allocation, thus prioritizing more vulnerable households.

Despite the above supports for low incoming households, keeping rents affordable is a challenge in all three countries, and this is likely to be a growing concern, primarily due to escalating land costs. The consequences of higher rent levels is that (a) there is a greater need for state subsidies of one sort or another and (b) low income tenants may struggle to access housing in the sector. With regard to the latter issue, municipalities often play an important role. In the Danish case, as noted, this happens via their role in allocating tenancies. In the Austrian case, municipally owned cost rental housing tends to be targeted more at low income or vulnerable households. In any event, there are a wide variety of supports for low income households that we can learn from here in Ireland. Moreover, Ireland is in the unusual position of already having a reasonably large social housing stock which caters for the most vulnerable households. Although it goes without saying that this stock needs to increase greatly, it should take the edge of some of the challenges associated with moderate-to-high rents in our cost rental sector.

Events

Not an event as such, but the Housing Agency has launched the Housing Unlocked competition, which calls on people to come together to create solutions to our housing crisis. The Irish Council for Social Housing have announced this year’s Finance and Development conference will take place October 19/20.

What I’m reading

Two very important new reports this week. This one from the CACHE looks at the evidence base around rent controls (an issue I looked at here). And this one from AHURI looks at the relationship between precarious housing and well-being. The Parliamentry Budget Office published Housing Ireland: Trends in Spending and Outputs of Social and State Supported Housing 2001-2020.