Building Adaptably: Future proofing Irish cities

The Week in Housing 05/12/25

This week I’m delighted to bring you a guest post by Joseph Kilroy, Policy & Public Affairs Manager with the Chartered Institute for Building. The below presents new research and an innovative approach to simultaneously tackle vacancy, supply and sustainability concerns. I had the chance to read through the whole paper already, and it is well worth a look. Joe’s previous post for The Week in Housing developed the idea of ‘green property flipping’. If you work in the housing sector and are interested in writing a guest post please get in touch, details here.

The evolution of a city’s physical form and the fortunes of its buildings are influenced by a range of economic, social, political, legislative and environmental forces that change over time. In ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’ Jacobs observes that: ‘time makes the high building costs of one generation the bargains of a following generation. …time makes certain structures obsolete for some enterprises, and they become available to others.’

A few facts about Ireland’s cities suggest that time is moving faster than our buildings can cope:

· Ireland’s national commercial vacancy rate (14.5%) is the highest on record

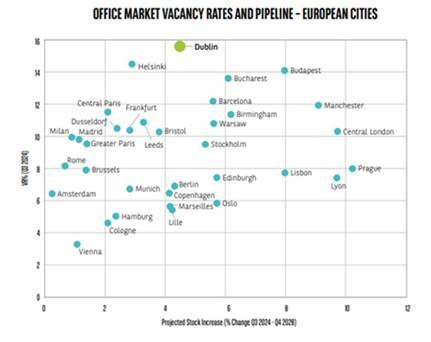

· Dublin’s office vacancy rate reached 15.7% in 2024 — the highest level of any major European city.

· Office vacancy in Ireland is concentrated in the areas where housing need and demand is highest.

The speculative commercial building model has resulted in an incongruity in our cities between what is being delivered and what is needed. This is marked by office vacancy rates reaching all-time highs across Dublin, Galway, Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Belfast. Meanwhile, each of these cities experiences a concurrent shortfall in housing supply in the very areas where offices lie vacant.

And it is not just the data - the experience of residents is telling the same story. Our survey of 4000 city dwellers for this report found that nearly two thirds of respondents (64%) said they do not believe new construction is building what their city needs, and over half (52.5%) said their area has an issue with a surplus of offices.

There are several structural factors underlying the long term fall off in demand for office space, in particular changing work practices, and a contraction of the tech sector since mid-2022. Having spiked during the pandemic, the incidence and intensity of remote working stabilised in 2024 with the proportion spending most of their time outside the office stabilising at 58%. Further, a correction of the stock market in 2022 has led to a contraction in the tech sector globally, leading to shrinking workforces and less demand for office space. The spatial impact of this contraction was particularly felt in tech heavy cities such as Dublin, where tech firms accounted for 51% of new office leases between 2017 and 2021.

In short, time has moved on and our building model has not.

Instead, a ‘present bias’ has emerged in the design of the modern built environment. This bias leads to the form of buildings being rigidly defined by immediate considerations, typically led by economic demand cycles, rather than more context-oriented and time-based considerations that consider future as well as actual scenarios. Present bias is seen in the rigidity of how form relates to function in modern buildings; whether they are commercial, residential, industrial, educational, or cultural, new buildings are typically built to fulfil a single function throughout their life span.

Office market vacancy in European cities (Image courtesy of BNP Baribas)

Policy can correct this failure of the speculative building model, and ensure that new buildings meet the prevailing needs of society rather than speculative future demand. Rather than accepting vacancy as the cost of doing business, we see potential to address vacancy through design that supports adaptability, repair, and maintenance, in line with the indicators of a framework such as the EU Framework for Sustainable Buildings.

Adaptability

In the current ‘demolish and rebuild’ building paradigm, vacant offices in urban areas appear as wasted assets. But, flexible and positive construction and planning policies that embed adaptability requirements for new buildings can turn vacancy in the commercial segment of the market into an additional source of housing in the residential segment. This is particularly the case where there is a disequilibrium between the supply of office space and the demand for residential accommodation, as is the case in Ireland’s cities.

Our new report ‘Building Adaptability: How the construction sector can future proof Irish cities’ proposes to introduce adaptability metrics into the planning permission decision-making process. Assessing a building’s potential adaptability would ensure that new buildings are designed for the short, medium and long term..

Recent iterations of the London, Paris and Amsterdam city plans each show how planning policies that prioritise building adaptability can curb long-term vacancy and support urban housing supply. The 2021 London Plan calls for flexible, multi-use building typologies in growth areas, helping older commercial blocks transition into residential or mixed-use without costly retrofits. The 2021 Plan Local d’Urbanisme Bioclimatique de Paris has adopted proactive policies and financial incentives to convert obsolete office stock into housing, demonstrating how regulatory clarity can unlock large volumes of centrally located homes. Amsterdam’s zoning and design standards, as laid out in its 2025 Urban Policy, increasingly require new developments to be “future-ready,” ensuring buildings can shift between residential, commercial and community uses as demand changes.

Conditions for success

Encouragingly, Ireland’s cities exhibit the same core conditions that have enabled cities like London, Paris, and Amsterdam to adopt adaptable building models: high levels of office vacancy in the urban core; urban demographics shifting to smaller household sizes; and strong city level governance structures.

Office vacancy in Ireland is disproportionately concentrated in city centres—precisely where housing demand is highest—making these locations optimal for adaptive reuse. Demographic shifts toward smaller households further support the feasibility of conversions, which tend to yield smaller 1-2 bed units. Strong governance structures, particularly legally binding city development plans, give local authorities the tools to shape more flexible, future-proofed urban development. Taken together, Ireland’s economic, spatial, demographic, and governance conditions create an exceptionally favourable environment for the widespread adoption of adaptable building practices.

Recommendations

We make 4 policy recommendations, each of which would embed building adaptability into the design and construction of new buildings in Ireland’s cities. Recommendations 1 – 3 address city development plans, while recommendation 4 addresses national policy vis public land sales.

For City Development Plans:

1. Mandate that all new large-scale developments in the city centre demonstrate design adaptability using standardised assessment tools—such as EU Level(s) Indicator 2.3—to ensure long-term spatial and functional flexibility.

2. Require planning applications for large-scale commercial or residential projects to include renovation and conversion scenarios as part of their design proposals.

3. Incentivize the use of modular, demountable, and circular construction methods through fast-tracked permitting or density bonuses for developments that exceed adaptability benchmarks.

For National Policy:

4. Embed design-for-adaptability criteria into public land sales and procurement contracts to ensure that publicly funded or facilitated developments are future-proofed for changing uses.

Conclusion

The prevailing “demolish and rebuild” model— driven by short-term economic cycles and speculative expectations—has proved both environmentally and socially unsustainable. By contrast, embedding adaptability into the design and regulation of new buildings offers a practical and forward-looking means of aligning urban development with real demand, long-term sustainability, and climate resilience.

By adopting the proposed policy measures—mandating adaptability assessments, requiring conversion scenarios, incentivising modular construction, and embedding adaptability in public land development—Irish cities can create a more resilient, circular, and inclusive urban fabric. Such reforms would enable buildings to evolve alongside the societies they serve, converting underused assets into homes and communities rather than waste. In doing so, Ireland can move beyond reactive, speculative building practices toward a proactive, adaptable, and sustainable model of urban development fit for the 21st century.

Should measures to further encourage full utilisation of land and built environment such as:

1. Taxing empty office buildings as vacant properties to encourage rapid conversion to living accommodation. ?

2. Requiring all high rise office developments to contain a proportion of apartments to promote the full utilisation of investments rather than 9-5 city centres.

Hi Bud,

Thanks for engaging with the paper.

I can see the merit in these suggestions. 1. We need to incenvitise producitve use of land, and tax is an effective means of doing so. As we outline in the report, vacancy is paid for by the public in lost business rates, which typically fund urban service, so taxing vacant commercial buildings does seem a sensible way of clawing this public cost back while also creating an incentive to ensure that once a buildign is completed, it is occupied.

2. If our proposals were implemented, new high-rise developments would be designed so they can become housing where needed — but without predetermining the outcome, allowing cities to respond flexibly as needs shift over time.